The crayfish belongs to the Phylum Arthropoda, which includes organisms having an exoskeleton, jointed appendages, and segmented bodies.

The word “Arthropoda” literally means “joint foot.”

The anatomy of this animal can be studied as external and internal anatomies.

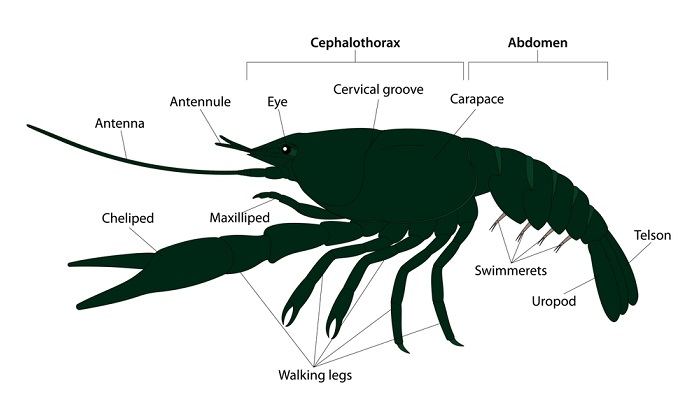

External Anatomy of Crayfish

Crayfish have two main body areas: the cephalothorax, which consists of the head and upper body, and the segmented abdomen.

Appendages can be found in both regions.

Head

The head has a set of eyes that are mounted on stalks called Pedicles.

These eyes can move independently.

The head also has two sets of antennas that help them gather information about its environment.

Around the head, three sets of small appendages exist surrounding the mouth.

These are called the Maxillipeds and are arranged so that one is on top of the other.

These appendages aid the crayfish in food manipulation.

Mandibles Structure and Function

- The Mandibles of crayfish resemble human jaws in function.

- But unlike in humans, these mandibles (the jaws) of the crayfish open from side to side.

- They are powerful enough to crack the hard shells of many small aquatic animals.

- Crayfish is a carnivorous animal and, in general, consumes fish as well as other invertebrates like crabs and shrimp.

Antenna Structure and Functions

These are of two sets the antenna, the longer and thicker ones, and the antennules, the shorter ones.

The antenna starts in the crayfish’s head, just behind the rostrum, and resembles wires.

They are long sensory protrusions from the cephalothorax part of the crayfish’s head that are used to detect food and touch.

These organs provide the senses of touch and taste.

The sensory bristles on the antenna are also thought to be capable of responding to sound waves in addition to touch.

Overall, the antennae assist the crayfish notice items in its environment and assessing its surroundings.

Antennules structure and function

The antennules are the smaller set and are significantly thinner and smaller than the antennae.

They are located below the rostrum and compound eyes.

Each of the two antennules that emerge from the crayfish is divided into two parts.

They are the crayfish’s cephalothorax section’s head region’s small sensory appendages.

They have a purpose in detecting items in the environment. They serve the purpose of the tactile sense.

They are able to detect food.

They aid in maintaining equilibrium and balancing the crayfish.

They support the senses of balance, taste, and touch.

The crayfish uses its antennules to perceive the environment and assess its surroundings.

Cephalothorax

The cephalic (or head) and thoracic (or chest) regions make up the cephalothorax (cephalic+ thoracic).

The chest is made up of three segments that are visible from the ventral side. Each segment has a pair of walking legs.

The carapace, a robust armor covering the internal organs and a portion of the head, is a part of the exoskeleton.

The rostrum is the portion of the carapace that extends over the head and in between the eyes in the cephalothorax region.

Abdomen

The segmentation and flexibility of the abdomen are evident here.

The crayfish’s appendages are joined to both the cephalothorax and the abdomen.

The walking legs are the protrusions that connect to the thorax, and the illustration below shows how they are joined.

Swimmerets are tiny appendages that are joined to the abdominal segments.

The crayfish in the photograph is female; males have bigger first swimmerets for gripping the female during copulation.

The crayfish’s big claw. The crayfish utilizes this jointed claw, known as the cheliped, to defend itself and to snare prey.

The telson, which has fan-like fins that extend to either side, is a unique segment that makes up the very last segment of the crayfish.

Crayfish can use their uropods to propel themselves through the water or walk on the bottom of a lake or ocean.

Since they move so quickly, crayfish can be surprisingly challenging to catch.

Internal Anatomy of Crayfish

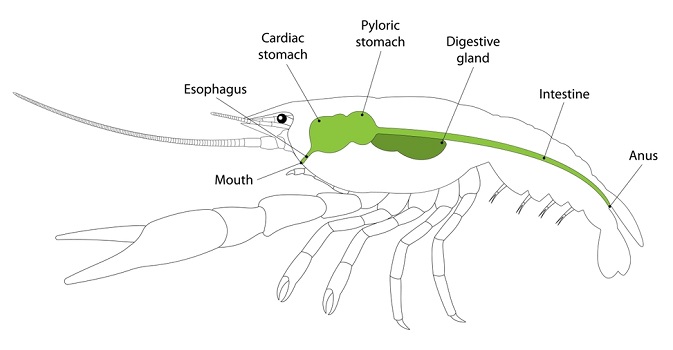

Alimentary Canal

The crayfish’s alimentary system can be divided into three basic parts like the

- The esophagus and foregut

- Midgut, and

- Hindgut.

The midgut is endodermal derived and is lined with a non-chitinous, columnar epithelium,

The esophagus, foregut, and hindgut are ectodermal derived and have chitinous linings.

The hepatopancreas, a massive, lobed digestive gland, surrounds the foregut, which is situated dorsally in the cephalothorax.

In certain crayfish species, the hepatopancreas may almost wholly fill the dorsal portion of the thorax.

Additionally, the midgut and hindgut may have different blindly terminating tubules or ceca along their entire length within the abdominal somites.

The three regions of the alimentary canal’s main characteristics are discussed below.

The Foregut and Esophagus

Food travels directly into the foregut from the mouthparts through the J-shaped esophagus.

In conjunction with the extrinsic musculature, the esophagus may be thrown into longitudinal ridges or chitinous folds, which may limit the lumen’s size and ostensibly prevent the regurgitation of food.

The foregut of crayfish is a dual-chambered, chitinous sac that varies considerably.

The area closest to the front, the cardiac chamber, is a sizable sac in the majority of a diversity of interior structures in crayfish species that allegedly make meal sorting and mastication easier.

The cardiovascular pyloric valve divides the posterior pyloric chamber from the cardiac chamber.

The pylorus is separated between an area at the top that connects to the midgut and an area at the ventral end that leads to the gland, a straining device, a filter, or an ampulla which only allows the tiniest particles to reach the hepatopancreas or digesting gland.

The chitinous plates or ossicles that make up the cardiac and pyloric chambers vary in number and have different sizes and morphologies.

The ossicles are connected to one another by membranous ligaments permitting movement by the extrinsic musculature that controls actions on the foregut.

The cardiac Chamber

The roof of the cardiac chamber is composed of the anterior, unpaired mesocardiac ossicle, paired pterocardiac ossicles, paired lateral zygocardiac ossicles, and the unpaired centrally placed urocardiac ossicle.

The urocardiac ossicle extends internally to form the median tooth.

The lateral teeth arise from the zygocardiac ossicles. Presumably, the action of the lateral teeth grinding against the central median tooth masticates food by forming a “gastric mill.”

Pyloric Chamber

Usually smaller and narrower than the cardiac chamber and is composed of the unpaired pyloric ossicle, which butts against the urocardiac ossicles.

Directly posterior and connected to the pyloric ossicle is the uropyloric ossicle.

A pair of exopyloric ossicles may (uncommonly) flank the usually broadly rounded pyloric ossicle.

The roof of the pyloric chamber may be variously modified depending on the species’ diet.

In those decapods that filter feed, such as species within the caridean shrimp genus Atya, a dorsal median projection, borne on the uropyloric ossicle, projects into the chamber.

The median projection is continuous with a complex series of thin chitinous folds, the convoluted membrane, which fills the posterior two-thirds of the pyloric chamber.

The hepatopancreas

The hepatopancreas, also known as the digestive gland, is a sizable, bilobed organ made up of numerous tubules with blind ends.

This crucial organ is involved in the digestion of food, the transport of food, the release of digestive enzymes, and the storage of lipids, glycogen, and various minerals.

Respiratory System

Crayfish have gills attached to their front legs in the thoracic chamber of their chests.

At the tips of the legs or where body shells and legs meet, they resemble feathery patches.

The structure of the gills, which require a large surface area to absorb the most oxygen from the water flowing over them, is what gives fish their feathered appearance.

Crayfish have gills that are primarily designed to breathe underwater.

They are free to remain submerged for as long as they want. As long as the water is oxygenated, they will live.

These gills can be seen on the crayfish’s sides and at the base of appendages.

They can be identified by their fuzzy grey or brown appearance.

While water flows through a crustacean’s gills, oxygen is absorbed into the bloodstream, but these gills are capable of much more.

Excretory System

Crayfishes have the antennal gland (green glands) and the maxillary gland, two distinct excretory organs.

Both have an end sac and a convoluted duct, which may expand into a bladder before opening to the outside, as their basic components.

Only one or the other gland functions in the majority of adult crustaceans.

During its life cycle, the functional gland may change.

The antennal and maxillary glands primarily regulate ionic balance.

The gut, which can absorb both, also regulates the overall balance of salts and water.

Glucose reabsorption by the antennal gland has also been demonstrated.

Most crayfish excrete ammonia through their gills as a by-product of nitrogen metabolism.

Urea, or uric acid, produced by some of the more terrestrial forms, is much less toxic than ammonia.

Urea and uric acid can be either excreted without losing a lot of water or stored in special large cells close to the bases of the legs.